Originally published in ColdType | Issue 218 | January 2021

For eight months, I endured the Covid lunacy by traveling from one end of America to the other. It was way more fun than I dare admit to anyone who quarantined the entire time. From New England to Appalachia, from the Sonora Desert to the Pacific Northwest, I enjoyed the finest natural history tour of my life.

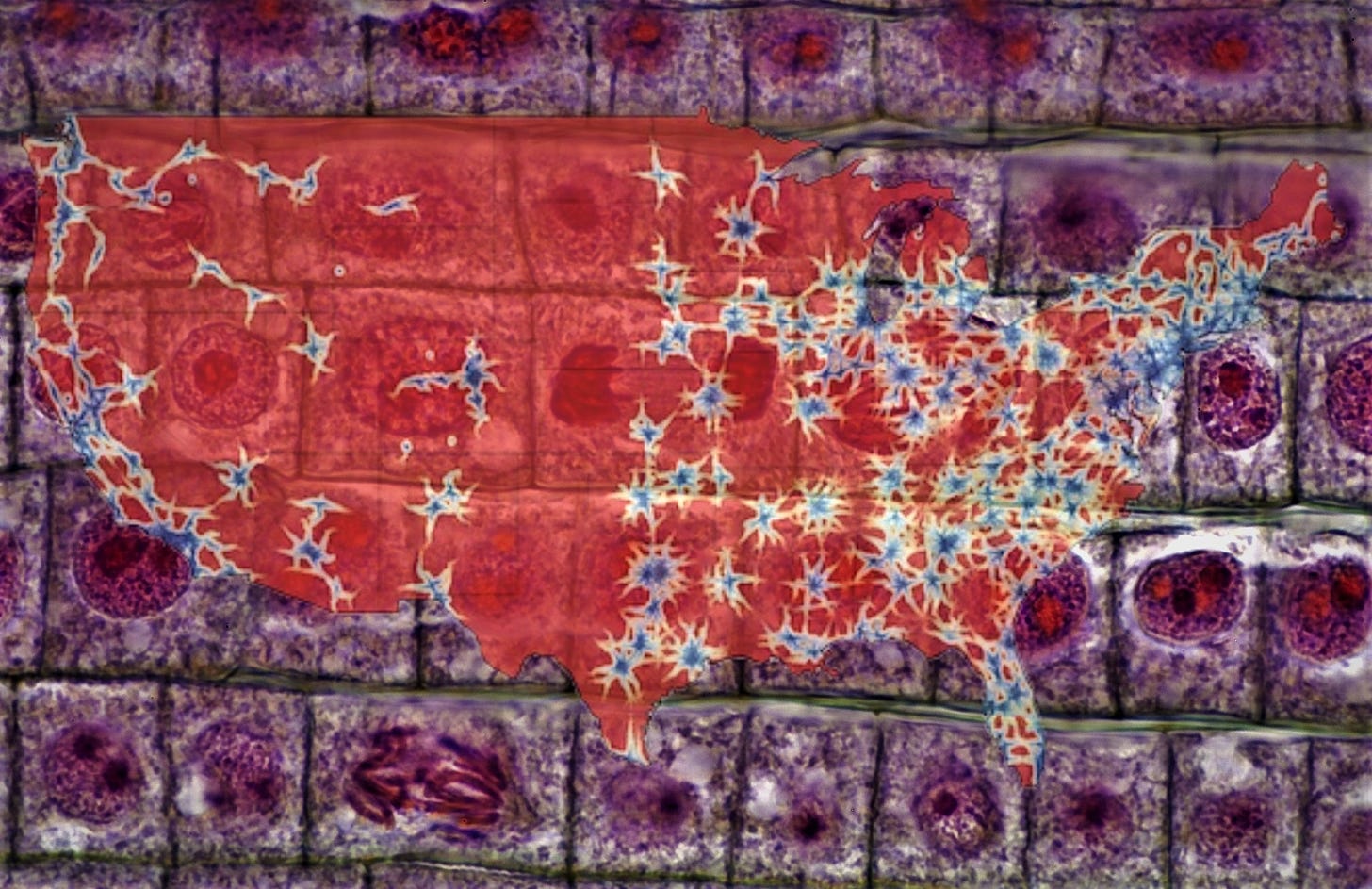

I did my damnedest to outrun the masked pod-people. It was like getting chased by prions through the hollows of Uncle Sam's rotting brain. They finally caught up to me in the northern Rockies. Presently, in every blue city (and half the red ones), you'll find pod-people shambling down the street—all alone, out in the sunshine—sporting fashion masks to simulate altruism for their fellow Covidians.

Looking back, it’s hard to believe our rulers ever let us go where we wanted and do what we pleased.

Looking ahead to increasing surveillance, corporate monopolies, nit-picky control mechanisms, citizen snitches, cartoon-like polarization, mandatory tracking-devices, random checkpoints, immunity passports, and vapid entertainment, I'm bracing for a dismal spell in world history.

The novel virus will pass soon enough. In time, the dead will be properly mourned. But this dark wave of technocratic constraint isn't going anywhere. The desire for top-down control is too tempting to resist.

The sun rises all the same. No matter how much power the corporate Leviathan acquires, no matter how tight its grip, the will to freedom is innate. Living things always fight for air.

—

Anti-Vaxxers in Great Barrington, Mass.

My jaunt across America began in the Berkshires, out in western Mass. I arrived by way of Indonesia, Thailand, and Oceania. I'd been working abroad and hanging around the temples of foreign gods, as is my custom.

I returned to Massachusetts just before the 2020 new year. After two months in the tropical breeze, the winter chill hit hard. The little town of Great Barrington felt like a cosmopolitan nursing home flanked by organic farms, a weed dispensary, and a couple of non-traditional grade schools.

The town also hosts “The Largest Asian Store in America.” Out in the parking lot, you see 20-foot high stone Buddha heads gazing at the ski slopes across the way. Inside, the multi-cult gallery is crammed with intricately carved Hindu idols and wooden Tantra wieners.

I visited this pillaged bazaar just before the Great Germ Panic of 2020 broke out, back when a nakedface could still roam around freely.

The diminutive owner was a real go-getter. In his former career as a “trained epidemiologist,” he would pick up artwork from all over Asia and sell it back home in the US. As his business boomed, he went from public health expert to world religion expert, with more than enough ego to make up for gaps in his knowledge.

Turns out we had a lot in common.

“It kills me when white expats come to Bali and get put off by the local rituals,” he fumed. “Animal-rights types tried to outlaw animal sacrifice on the island!”

“Think of how Londoners feel when Muslims arrive and demand the British legal system to accommodate Sharia,” I replied.

Typical of his caste, he refused to see the connection. Before long, our conversation turned to the anti-vaxxers who populate the Berkshires. These aren't trailer park people, he told me. These are wealthy liberals who want other people's kids to risk adverse side-effects, keeping their own kids safe from both the vaxx and the measles in one shot.

Seems pretty clever to me.

A lot of these anti-vaxxers are part of the Anthroposophist Society—a Western esoteric sect. Their German founder, Rudolf Steiner, pioneered organic farming in the early 1900s, and developed the Waldorf school system as an alternative to the industrial education model. Steiner also claimed to see auras and various otherworldly beings.

“This is why we're seeing measles outbreaks!” the shop-owner yelled, punching his tiny fist into his palm. “These people are anti-science!”

“I get vaxxed whenever I have to. But still, I can understand people's hesitation—”

“I can't,” he snapped. “It puts other people’s lives in danger!”

“When I was a kid,” I said, “my friend’s little sister got the measles shot and had a bad allergic reaction. Her fever shot up and her brain swelled. After the reaction subsided, she was permanently disabled. She never spoke another word and had to be pushed in a stroller for the rest of her life—”

“That's just an anecdote. You don't know if the vaccination caused it.”

“Of course. But the timing was enough to convince her parents. The kid's fever was sky-high—”

“Vaccines don't cause fevers!”

I stood there, blinking, as did the Hindu gods on the shelves.

“Dude! Every time I’ve been vaxxed, the nurses warned I’d get a fever. Every time. They said it’s normal.”

“My kids never get fevers.”

“Okay. But—”

“I'm a trained epidemiologist and...” On and on he went, oblivious. Something about “the social contract” and “more science education”—the usual.

I was stunned any “expert” would deny vaccines cause fevers, but it turns out that “trained epidemiologist” was just a taste of the medicine we'd all be swallowing.

Plain Churches in Lancaster County, Penn.

Just before the Germ Panic shut down the world, I was working at the Rock Lititz rehearsal venue way out in Amish country. Curious about the locals’ archaic ways, I set out to find one of their churches.

It turns out you don't just wander into an Amish church. For one thing, services are typically held in family homes. For another, the hymns and liturgy are in Pennsylvania Dutch. And because the Amish take great pains to keep their culture pure, they don't like curious strangers poking around their sacred gatherings.

After days of pestering the townsfolk, I finally got myself invited into a different “plain church” community—the Brethren—who share much in common with their Amish, Quaker, and Mennonite neighbors.

Brethren men wear black hats and suspenders, their women wear big bonnets, and many say “thee” and “thou” as if nothing has changed since King James. The Brethren are also pacifists. No violence allowed, no matter how bad it gets.

If a man strikes you on one cheek, by God, you turn to him the other. Higher powers will handle it.

Like their old-school neighbors in cattle-n-corn country, many Brethren are farmers and skilled craftsmen. They're admirably self-sufficient. Their children are taught the old ways in small wooden schoolhouses. Unlike the Amish, though, the Brethren readily adopt certain practical technologies—cars, tractors, telephones, eBibles—but they forbid the sinful entertainments of the wider culture.

That means they’ve never been exposed to real comedy, so they’ll laugh at any joke you throw at ‘em. You can be like — “That's when the city boy said: ‘Is that a haybale or a horseshoe?’” — and have em’ rolling in the floor.

One Sunday morning, this Brethren elder drove miles out of his way to pick me up for church. He introduced me to everyone, and I mean everyone. When things got started, someone handed me a hymnal. As the congregation lifted their voices, this Abe-bearded ogre in the next pew sang as loud as possible, drowning everyone out with his single steady off-key note.

The sermon was about tolerance.

Afterward, a bunch of us went back to the minister’s house for lunch. Three generations of Brethren gathered at a long table. They asked me questions like I was a spider from Mars. No matter what I said, the entire family cracked up laughing.

They all looked so similar—strong hands, rosy cheeks—except for this quiet African girl, unusually tall, whom the minister and his wife had adopted on a missionary trip to Ghana. Over the years, this couple has spread the gospel from India to China to South America.

After lunch, the house matron showed me her vast collection of plastic cows. Most were housed in a fine, hand-made China cabinet. Later, the patriarch took me down worn wooden stairs into the cellar, where he had an elaborate model train set. He’d created an entire miniature village. There were patrons browsing shop windows, farmers plowing wheat fields, and grimy men working the rail station.

There was a nasty car wreck at the town’s main intersection. Two cars had hit each other head on. A dead body was sprawled out on the pavement. A dog stood barking at the wreckage.

“That poor guy should've stuck with the horse-n-buggy, eh Mordecai?”

The old fellow doubled over in a belly laugh as the little train went round and round. I shook my head. Off in the shadows, his pudgy grandson eyed me suspiciously.

It pained me to leave that old house. A sense of homesickness followed me out the door—a deep need to return to some place I've never really been.

—

Rogue River Gorge, Ore.

After years of wandering the Oregonian mountains, I finally saw a raptor pull a fish out of the river. Our group was packed into two big rubber rafts, with a few scouts in kayaks. Most were hippies—a Caucasoid dreadie, a Cascadian rasta, a spun-out Indian, a cute Colombian woman, the Prince of Persia. The alpha dog handed out magic mushrooms as a matter of hospitality, with canned beers to wash ‘em down.

As we cruised down the river, a bald eagle swooped in and hit the water with masterful precision, pulling up a massive salmon with barely a splash. My third eye was pried wide open, half-blinded by the sun's sharp rays. You could see the life force flow from fish to bird. Both creatures were synced to the greater movement around us.

Later on, we discovered rows of cliff swallow nests cemented to the rock under a craggy overhang. We paddled over to invade their territory. Tiny chicks cheeped in their clay fortresses, and the adults whirled up into an aggressive bird tornado, forcing us to retreat.

Down around the bend, we saw an osprey come in for the kill. It was diving toward the river, claws outstretched, when out of the blue came an ornery cliff swallow. The smaller bird swooped in on the osprey—not touching him, just psyching him out—and the raptor missed his prey. The little bastard even turned around to whistle as the osprey flew off empty-handed.

The whole scene put me in a brilliant mood. That cliff swallow came from nowhere just to fuck up an osprey's day. Just for the hell of it.

Nature loves a belly laugh.

That night, the hippies played guitars and congas. They sang about world peace and other imaginary beings. Their smiles glowed in the campfire. I stared into the flames.

If hell is other people, you can damn me to hell.

—

A Lone Wolf in Nashville, Tenn.

During the six years I lived in Nashville, I saw that river town slide farther and farther downhill. The economic crash of 2008, followed by the flood of 2010, corroded the charming sections of the city. With the subsequent flood of Yankees and Coasties, big capital poured in from north and west, drowning out the gritty character.

Within a decade, global companies had built a strong corporate infrastructure in the heart of Tennessee. Incoming hordes kicked off a traffic jam that hasn't budged in five years. Music Row was gutted. The skyline—once dominated by brick facades, tacky neon, and the big Bat Building—suddenly mutated.

Today, the cityscape is defined by McSkyscrapers, a Bezosian borg cube, and long rows of Crayola condos. Last time I passed through, just after Election Day, the city felt like a half-finished Disney theme park where the lines never move. The familiar faces were replaced by plastic cowboys and bleached L.A. transplants.

It looks like things will just get weirder from here. On Christmas morning of 2020, news broke that an RV had exploded—Baghdad-style—down on 2nd Ave. Watching the surveillance footage, you can hear a robotic female voice warning residents of immanent danger.

"This area must be evacuated now," she repeats, over and over, concluding with, "If you can hear this message—evacuate now." Then... BOOM! Everything blown to shreds.

Before you could say “lone wolf,” the perp was identified as 63 year-old Anthony Quinn Warner, a tech-averse IT guy from a nearby suburb. Bits of person were found near the blast zone. DNA analysis indicates Warner was inside the RV when it detonated. Apparently, he'd just signed over two overpriced properties to a pretty 29 year-old living in Los Angeles. He also told an ex-girlfriend he'd been diagnosed with cancer.

Warner's suspected target was the 15-storey AT&T building. Rumor has it that Warner's father, who died years ago, worked for a company bought out by AT&T.

The Tennessean called Warner a “self-employed computer guru.” The FBI claims that the mullet-sporting misfit was freaked out by encroaching 5G networks and the specter of mass surveillance. Some say he was worried about reptilians taking over.

The camper-bomb took out phone networks and Internet service for a short time. I’m told that WiFi junkies circled McDonald’s parking lots like vultures, seeking connection.

No one but Warner was killed. If history is any guide, the only lasting effects will be on civil liberties. As with self-preservation or a sense of humor, the desire for privacy will be pathologized.

Look for more police checkpoints on Broadway, and heavy-handed crowd control. Have your ID ready. Look for overzealous cops shaking down songwriters who busk without a permit. Look for RV-gypsies to be portrayed as a public menace. Look for bland Lego blocks to replace the scorched brick buildings on 2nd Ave.

Look for drones overhead. Look for more cameras looking back at you.

From now on, nothing happens out of sight. Not bar fights. Not smoke sessions. Not making out in a dark alley. If you want to paint the town red, expect your best and worst moments to go on your permanent record.

Think of it as getting a state-sponsored selfie.

If the 21st century response to terrorism has taught us anything, it's that the Panopticon appears in the blink of an eye. It only takes one dumbass knocking over a single domino for the whole mess to come crashing down on our heads.

Originally published in ColdType | Issue 218 | January 2021

FOLLOW — Twitter: @JOEBOTxyz | — | FOLLOW — Gettr: @JOEBOTxyz

If you like the work, gimme some algo juice and smash that LIKE button.

"It pained me to leave that old house. A sense of homesickness followed me out the door—a deep need to return to some place I've never really been."

I couldn't have said 'it' any better. A lovely read.

That was a lovely read, partially because it was laced with just enough pathos and yearning for what beauty is still here and what we can see we will be losing shortly. At least that is what welled up in me, as I read your tale. It put me in mind of one of my favorite books, Blue Highways. You’ve a definite gift, and I look forward to reading more of your work.