The birth story of Jesus Christ is a sacred narrative, woven together from the divergent accounts of Matthew and Luke. As such, Christmas is a rite of reenactment, bringing the ancient Nativity scene to full consciousness. This miracle recurs each year in the Christian heart.

A virgin mother is visited by terrifying apparitions. A divine infant is laid in a feeding trough, heralded by angels and born under a portentous star. A sequence of Hebrew prophecies is fulfilled—the progeny of king David appears in Bethlehem, becoming the suffering savior foretold by Isaiah. A benevolent power arrives to transform a fallen world.

None of this makes sense, from a rational perspective, but that doesn’t matter. Sacred space and time are maintained by barriers against skepticism. Logical questions dissolve upon contact. These motifs didn’t appeal to intellect in the first century, nor do they make scientific sense today. They were never meant to.

“My kingdom is not of this world,” Jesus said. Faith endures beyond reason.

Even in ancient Greco-Roman society, haughty intellectuals disparaged the idea that God would incarnate in such a humble guise. For them, Christ was a crippled demigod for superstitious heathens, like Hercules or Dionysus—both sons of Zeus—but without the earthly glory.

Unlike Hercules, the preacher Jesus committed no heroic acts of violence. No monsters were strangled by his hands, and no enemy soldiers were struck down by his club—save for Jesus whipping money-changers outside the temple, or his own self-sacrifice on the cross.

Unlike Dionysus, the ascetic Jesus indulged no drunken orgies. He had no wild women chasing him through the forests. The closest parallels are the wedding at Cana, where he turned water into wine, or the prostitutes whom he transformed into respectable women.

Rationalists often use comparative mythology as a means to discredit religious faith. They point to all the miraculous birth stories found in the ancient world and say, “Look, the Nativity is just another story.”

In India, the Buddha was said to have been conceived miraculously, descending from Tusita heaven into his mother’s side in the form a white elephant. The moment he was born, according to the Jataka tales, he took seven steps and proclaimed, “For enlightenment I was born—for the good of all sentient beings.”

In the Mahabharata of the Hindus, the epic’s heroes, the five Pandavas, were the offspring of two queens made pregnant by the gods of Justice, Thunderstorms, and Wind, as well as the Twin Physicians to the gods.

Unlike the Buddha, though, whose victory was ultimate peace in meditation—or Jesus, whose glory was to defeat death on the cross—the Pandavas were demigods whose destiny was to exert worldly power through violence.

Fundamentalist theologians have a logical response to these tales, based on their literal interpretation of the Bible—“Our sacred story is true. Theirs are false.” No further questions.

Liberal theologians rationalize the similarities by saying “all religions are all equally true,” but the differences defy that reasoning. The exoteric truths in each tradition—the mythos and ethos—are clearly at odds with the others. As an illustration, the Nicene Creed only makes sense within the sacred boundaries of the apostolic Church:

We believe in one God, the Father Almighty. … And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only begotten Son of God, and born of the Father before all ages.

God of God, light of light, true God of true God. …

And we believe [in] one holy, catholic, and apostolic Church. We confess one baptism for the remission of sins. And we look for the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come. Amen.

The farther this image of Jesus travels from its own altar, the more it is defiled by the profane world outside—even as it encounters Protestant churches, let alone the temples of Hindus or Buddhists. The Word of Christ has an inherent power when spoken to an open heart. But the clarity of any traditional worldview, as a whole, recedes with distance from its own sanctuary.

In the hands of aggressive skeptics, comparative religion is wielded as a weapon against traditional Christianity. If the non-Christian stories are just made up, the reasoning goes, then the birth story of Christ is probably made up, too. And if all sacred narratives are just made up, we’re only left with the material world and our scientific method to explain it—or, failing an explanation, the raw power to control it.

More consequential, perhaps, is the conviction that if miracles are nothing but imaginative inventions, humanity’s only hope is in advanced technology. The Machine then becomes the highest power.

As rationalism and its deformed children, Marxism and Scientism, spread across the globe, the same strategy is used to subvert the sacred narratives of India, China, and the primitive tribes crushed under the wheels of industrial society. These secular revolutions were believed to be, as Nietzsche foretold, the Twilight of the Gods.

Yet religious faith persists in all these societies, among intelligent people, even as miracles are crowded out by the modern world. In the West, the faithful still gather in sanctuaries to celebrate the birth of Christ. Even for nominal Christians, whose day-to-day lives are devoid of sacred meaning, these periodic celebrations offer comfort and inspiration.

The Christmas rites reconnect us to our ancient past. At the same time, we glimpse a realm that transcends the structures and rhythms of nature. In the Nativity, we see a divine presence entering the world in an unexpected way—through a humble family in a Judean backwater—opening a story that defies normal logic and our desires for worldly power and physical survival.

According to Matthew, Jesus climbed up to the mountaintop and told his disciples:

You have heard that it was said, “An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.” But I say to you, Do not resist an evil-doer. But if anyone strikes you on the right cheek, turn the other also …

You have heard that it was said, “You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.” But I say to you, Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be children of your Father in heaven; for he makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the righteous and on the unrighteous.

What ordinary person could follow these commandments? They contradict our human nature. Perhaps that’s the point.

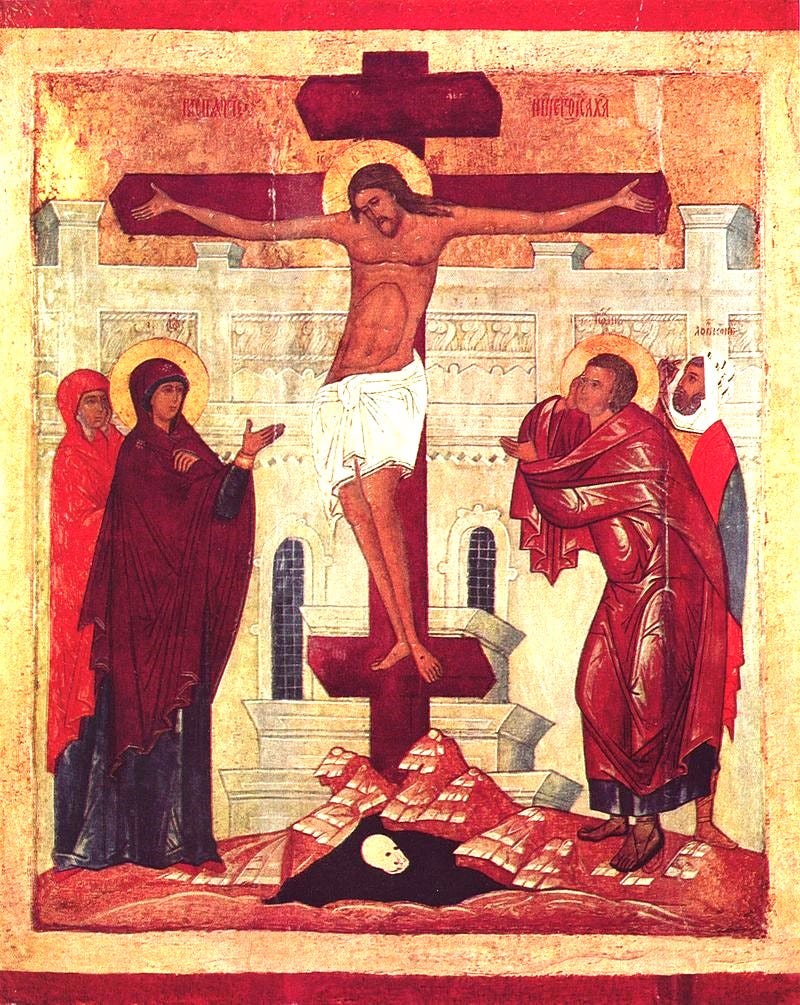

From the cross on Golgotha, the gospels of Matthew and Mark record Jesus’s last words as: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

In Luke, he says: “Father, into your hands I commend my spirit.”

And in John: “It is accomplished.”

Then the Son of God—the Word made flesh—perished and was buried.

According to the gospel of John, when the resurrected Christ returned, the apostle Thomas—“the Twin”—refused to believe it was true until he touched the wounds for himself. “Blessed are those who have not seen,” Jesus said to him, “and yet have come to believe.”

Alongside the Nativity, these sacred stories present a puzzle whose pieces don’t fit perfectly. It can only be solved by the heart. The rational mind will never grasp it.

Most good things in life are illogical. Science has found biological correlates to love, but the magic of passion and the strength of devotion are hardly explained by evolved instincts or oxytocin hormones. Reason tries to dismiss synchronicity as mere “coincidence.” Yet when symbolic forms break through into reality, the power is undeniable.

In Tertullian’s argument against the Gnostics, De Carne Christi (“On the Flesh of Christ”), the church father embraced the paradox as proof:

The Son of God was crucified: I am not ashamed—because it is shameful.

The Son of God died: it is immediately credible—because it is ridiculous.

He was buried, and rose again: it is certain—because it is impossible.

Many centuries later, modern skeptics would shorten this credo into “I believe because it is absurd.” They hurled it as an insult to the faithful. Given the demands of the cross, who could blame them?

As I contemplate the mystery of the Deity incarnate—born to a virgin, laid in a feeding trough, the ruler of an unearthly kingdom, who conquered infernal powers by dying—the entire story is patently absurd. Yet somehow, it is fitting.

A casual survey of our ordinary world shows that life is absurd. And so despite the nagging voices of logic and reason, I believe in the divine—even as I struggle to grasp it.

Merry Christmas, legacy humans.

An absolutely fantastic read, thank you. A real Christmas feast for the soul. I wanted to let you know that in June 1996, I encountered the 'star'. Incredibly, it said these exact words to me 'is not of this world,”' and I understood in a flash the temporal world in which I was in and that of eternity. Im positive that the star carried and transmitted divine knowledge. For the shepherds they followed a moving star, yet I was followed by the 'star'.

Beautiful! Thanks for the inspiration. Merry Christmas to you too!